Literature

Andersson, G. B. J., Murphy, R. W., Ortengren, R., & Nachemson, A. L. (1979). The influence of backrest inclination and lumbar support on lumbar lordosis. Spine, 4(1), 52–58.

Alexander, L. A., Hancock, E., Agouris, I., Smith, F. W., MacSween, A. (2007). The response of the nucleus pulposus of the lumbar intervertebral discs to functionally loaded positions. Spine, 32(14), 1508–1512. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e318067dccb

Bailey, D. P., & Locke, C. D. (2015). Effects of brief walking on postprandial glucose levels in overweight men. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 12(8), 1071–1075. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.12.8.1071

Beach, T. A., Mooney, R. A., & Callaghan, J. P. (2003). The influence of prolonged sitting on lumbar spine kinematics: A pilot study. Journal of Biomechanics, 36(4), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9290(02)00484-2

Bridger, R. S. (2019). Ergonomics: Foundations and applications. CRC Press.

Callaghan, J. P., & Dunk, N. M. (2002). Low back pain: A study of the relationship between lumbar posture and muscle activity. Clinical Biomechanics, 17(8), 546–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(02)00023-7

Dowell, J., Barlow, J. W., & Devereux, J. (2001). The effects of chair design on user posture and comfort. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 28(3), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-8141(01)00022-4

Ellegast, R. P., Kraft, K., Groenesteijn, L., Krause, F., Berger, H., & Vink, P. (2012). Comparison of four specific dynamic office chairs with a conventional office chair: Impact upon muscle activation, physical activity and posture. Applied Ergonomics, 43(2), 296–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2011.06.005

Fewster, K. J., et al. (2019). The effectiveness of sit-stand desks for improving occupational health and safety: A systematic review. Applied Ergonomics, 78, 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2019.04.015

Grooten, W. J. A., Conradsson, D., Ang, B. O., & Franzén, E. (2013). Is active sitting as active as we think? Ergonomics, 56(8), 1304–1314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2013.812748

Halim, K. F., & Rahman Omar, N. (2012). The effects of prolonged standing on posture and muscle activity: A review. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 18(2), 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2012.11076978

Hey, H., Teo, A., Tan, K., Ng, L., Lau, L., Liu, K., & Wong, H. (2017). How the spine differs in standing and in sitting-important considerations for correction of spinal deformity.. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society, 17 6, 799-806 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2016.03.056.

Holm, S., & Nachemson, A. (1983). Variations in the nutrition of the canine intervertebral disc induced by motion. Spine, 8(8), 866–874.

Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. (2007). ANSI/HFES 100-2007: Human factors engineering of computer workstations. American National Standards Institute. https://www.xybix.com/hubfs/ANSI_HFES_100-200727E2.pdf?t=1508538849931

Léger, B., et al. (2023). Dynamic sitting: A systematic review of the effects on comfort and muscle activity. Ergonomics, 66(3), 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2022.2089051

Lord, M., Small, J., Dinsay, J., & Watkins, R. (1997). Lumbar Lordosis: Effects of Sitting and Standing. Spine, 22, 2571–2574. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199711010-00020.

Makhsous, M., et al. (2003). Effects of seating posture on spinal alignment and muscle activation in the lumbar region. Clinical Biomechanics, 18(5), 491–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-0033(03)00011-7

Makhsous, M., Lin, F., Hendrix, R., Hepler, M., & Zhang, L. (2003). Sitting with Adjustable Ischial and Back Supports: Biomechanical Changes. Spine, 28, 1113-1121. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BRS.0000068243.63203.A8.

Mansoubi, M., et al. (2015). The effects of breaking up prolonged sitting on blood glucose levels. Physiology & Behavior, 149, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.04.027

McGill, S. M., Hughson, R. L., & Parks, K. (2000). The relationship between seated posture and low back pain: A review of the literature. Applied Ergonomics, 31(3), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-6870(00)00004-4

Merritt, J. L., & Merritt, J. L. (2017). The impact of prolonged sitting on the musculoskeletal system. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 29(6), 1001–1005. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.29.1001

Nazari, J., Pope, M. H., & Graveling, R. A. (2012). Reality about migration of the nucleus pulposus within the intervertebral disc with changing postures. Clinical Biomechanics, 27(3), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.09.011

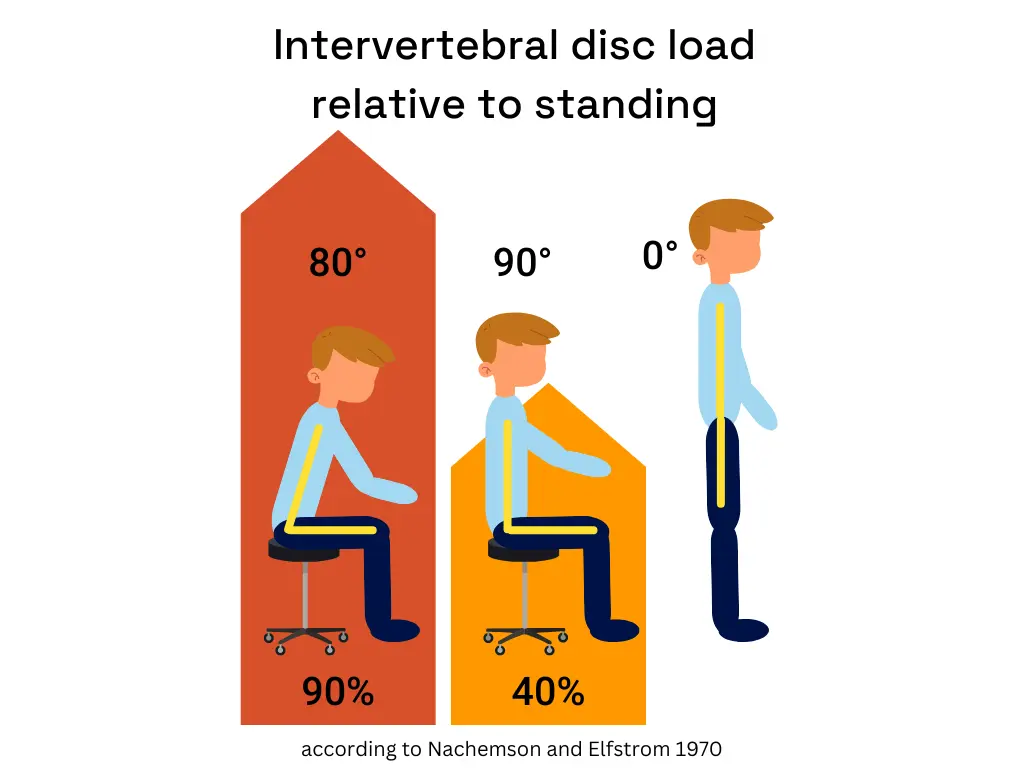

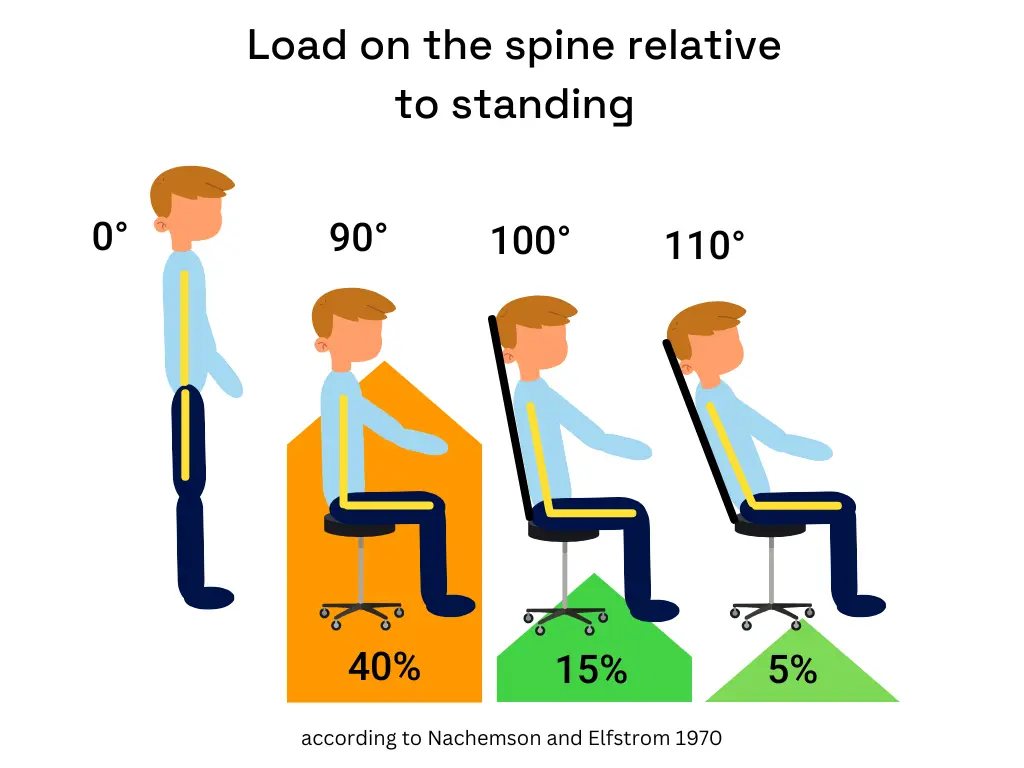

Nachemson, A., & Elfström, G. (1970). Intravital dynamic pressure measurements in lumbar discs. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, Supplement, 1(1), 1–40.

O’Sullivan, P. B., et al. (2010). The role of the lumbar spine in the generation of low back pain. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, 23(3), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-2010-0234

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (n.d.). Computer Workstations eTool. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.osha.gov/etools/computer-workstations

Pearse, S., Léger, M., Albert, W. J., & Cardoso, M. (2024). Active workstations: A literature review on workplace sitting. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, 38, 406–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2024.01.001

Pynt, J., Mackey, M. G., & Higgs, J. (2008). Kyphosed seated postures: Extending concepts of postural health beyond the office. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 18(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-008-9123-6

Schäfer, K., Müller, R., & Schmidt, H. (2015). The impact of static sitting on intervertebral disc nutrition: A biomechanical study. Journal of Biomechanics, 48(12), 2345–2351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.06.015

Stein, P., Yaekoub, A. Y., Ahsan, S., Matta, F., Lala, M., Mirza, B., Badshah, A., Zamlut, M., Malloy, D., & Denier, J. E. (2009). Ankle exercise and venous blood velocity. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH08-09-0615

Strand, L. I. (2000). The prevalence of back pain and associated factors in a working population. Occupational Medicine, 50(5), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/50.5.325

Triglav, J., et al. (2019). The impact of prolonged sitting on health outcomes: A systematic review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1162-y

Vergara, M., & Page, A. (2002). Relationship between comfort and back posture and mobility in sitting-posture. Applied Ergonomics, 33(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-6870(01)00056-4